Vasily „Gudred“, our craftsman of choice for anything that glitters, has made a new replica of a round fibula found in Birka.

Weiterlesen

Vasily „Gudred“, our craftsman of choice for anything that glitters, has made a new replica of a round fibula found in Birka.

WeiterlesenThis night, I was alerted by my friend Gudred to a posting made by Sergey Kainov, senior researcher at Moscow’s State Historical Museum[1]Sergey Kainov profile page, available online: https://shm.academia.edu/SergeiKainov, about an interesting piece in an online auction site.

The piece of jewelry is a viking-age „weather vane“ of which many examples exist. Tomas Vlasaty has taken great pains at cataloguing them here: Scandinavian weather vane jewelry (CZ) [2]Tomas Vlasaty, Skandinávské spony s korouhvičkou, available online: http://sagy.vikingove.cz/skandinavske-spony-s-korouhvickou/

The weather vane is gilded silver and rather typical for this kind of item. Its usage is atypical though – the evidence usually pointed towards these items being used as dress pins, much alike to the „Birka Dragon“ pin, as shown in these two reconstructions made by Gudred.

The silver chain and rings look like something which could have been made in the viking age. The chain is classified as „Type 6“ by Arwidsson in Birka II:3[3]G. Arwidsson, „Ketten“, Birka II:3, pp73-78, here: p74. Kugl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, 1989. ISBN 91-7402-204-0, and it is the third most frequent type of chain in Birka (with 12 finds from the graves).

The chain terminals could be from the viking age, too. However, they look a bit „off“ to me. A silver pendant like this, which was also gilded, was certainly an expensive piece, and re-using it as a pendant underlined that value.

The craftsmanship of the terminals, which are essentially cylindrical pieces of metal sheet, is not too impressive, and although it has some typical decoration (punched triangles with a dot in the center), I would say that it was maybe added at a later date, possibly in the medieval age. In any case, it’s my opinion that the chain and pendant is a secondary usage for the weather vane.

The piece is from „Lithuanian art dealership“, which is a quite shaky provenance. We have numerous examples of illegal looting in the Baltics and viking-age graves are especially affected by this. A piece in excellent condition like this one, with very peculiar properties, like this one, and an unclear provenance, like this one, looks „too good to be true“. I am unsure if the auction site offers more detailed documentation for prospective buyers, but I would be wary of this item.

I’m deliberately not linking the auction itself – if you want to find out about it, I am sure you can google it. 🙂

Is this an original? Is it a fake? Do you know of other finds like this (especially with these chain terminals)? Write me in the comments!

References

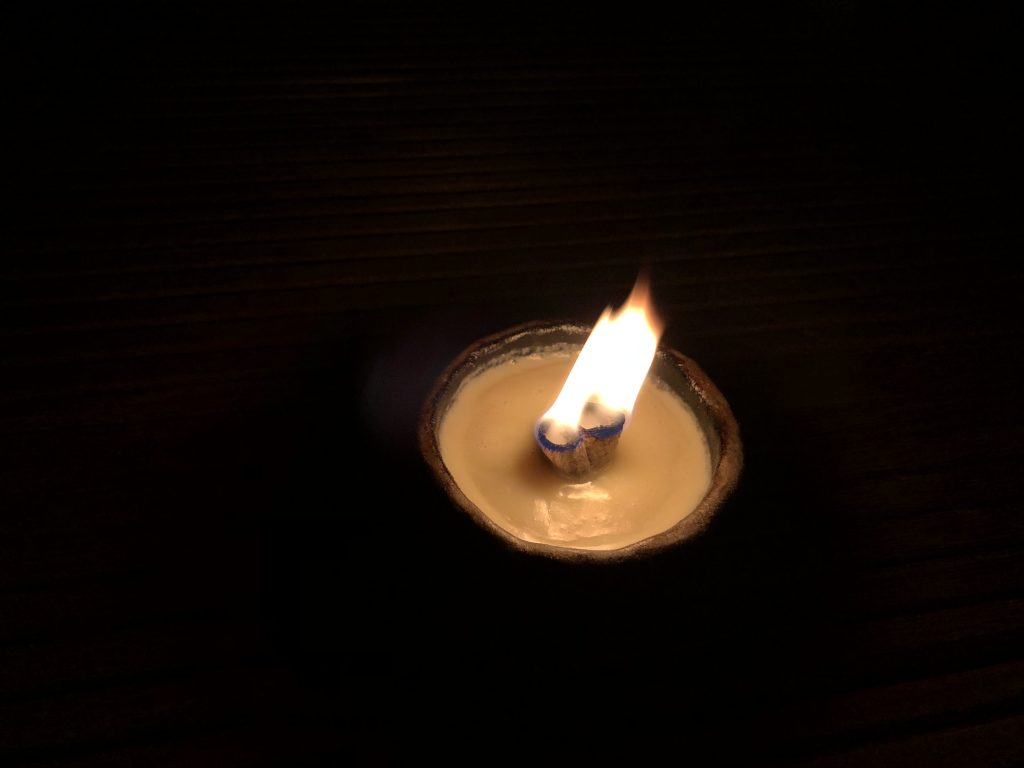

Some things that now seem hopelessly anachronistic and are dead cheap weren’t that cheap in former times. Artificial light, for example, was far from a commodity. Candles were, at least as far as we know, too expensive for everyday lighting, so viking-age buildings were sparsely lit. The central fireplace gave off some light, and there are several finds of items that held a liquid or solid fuel for lights.

This is a find from Birka, Black Earth (various identical lamps were found in Birka).

The fuel for these lamps was quite certainly animal fat, as vegetable fats (such as olive oil, linseed oil or other vegetable oils) were, and are, too expensive to burn, and have a couple of disadvantages. One of them is the fact that animal fat, especially pig and goose lard, or beef tallow, have a higher melting point, making them easier to handle.

I have one of these lamps as a reproduction, and for the past seasons, I used it with pig lard. This type of fat is readily available in supermarkets (it’s used for cooking), and is not too expensive. However, it’s not one hundred percent authentic and – which is really annoying – it turns liquid at room temperature, making summer events a really greasy affair if the lamp falls over.

I wanted to use beef tallow for a while now, but I never found any in butcher’s shops or supermarkets. Eventually, I thought „why not make it myself?“. We are lucky to have a really awesome farmer around the corner, who raises their own cattle (organic, by the way), and is in control of the whole butchering process. To add to this, they have a son in the same kindergarden as our kids, so I went there and asked if they could help.

Alas, they had no tallow, but they were just about to bring one of their Galloways to the butcher, and promised to set aside the fat around the kidneys, which is traditionally used to make tallow.

A week ago, I picked up these lumps of fat (around 4.5kg, one of two lumps shown). They have an interesting consistency – they aren’t greasy like bacon, instead they feel like wax. I put them in the garage to wait for better weather.

This saturday was a nice, sunny day, cold but great. I took lunch naptime as a welcome opportunity to light a fire in my outside fireplace and start making tallow.

First, I cut up the first lump into small cubes – and the cats loved the scraps that fell down in the process.

The next step was adding a little water and putting the cubes into the kettle. The water, I found out on the second run, is optional, I’d read that it makes rendering a little easier.

Now I let it heat up, waited until the water dissipated and started siphoning the tallow. It would have been a lot easier if I could just pour everything into a vessel, but the pot is really unwieldy and I didn’t want boiling fat all over myself.

For siphoning, I used a sieve that the kids play with. Had I wanted to make tallow for eating or cosmetics, I would have used some linen, or other fabric, to get clearer results. In this case, a sieve was enough.

I kept doing this several times, and the pieces of fat became increasingly crisper. I threw them back into the pot to increase the yield…

Eventually they were so crisp that they could only serve one more purpose…

…cat snacks! I am not usually a friend of high-fat diet for our cats, but there’s talk about a really rough couple of weeks (-20°C and so on…), and maybe a little extra fat will help them stay warm outside. Or they’ll have massive diarrhoea.

The yield of the day were 1.5 big glasses of tallow (I think one might have around two liters, but I’m not sure) and a plastic container (approx. 1 liter).

After a while, the tallow had cooled down and became about as hard as candle wax. I left it outside for natural deep freezing, but couldn’t wait to try it out. So i re-heated some of it in a small frying pan and quickly sewed a wick for my Birka light. At this point, I have to thank Katarzyna Masia Konkol for her very, very useful idea of putting a tubular wick over the cone in the middle. It works like a charm.

I took the light outside and lit it – and it works great!

If you can get your hands on cow kidney fat, try making tallow, it’s rather easy. The smell is not as bad as you might think (still, the dripping tallow is really annoying to clean, so better make this outside), and the yield is quite good. I spent less than 10 Euro on the fat, and it gave me 3+kg of tallow.

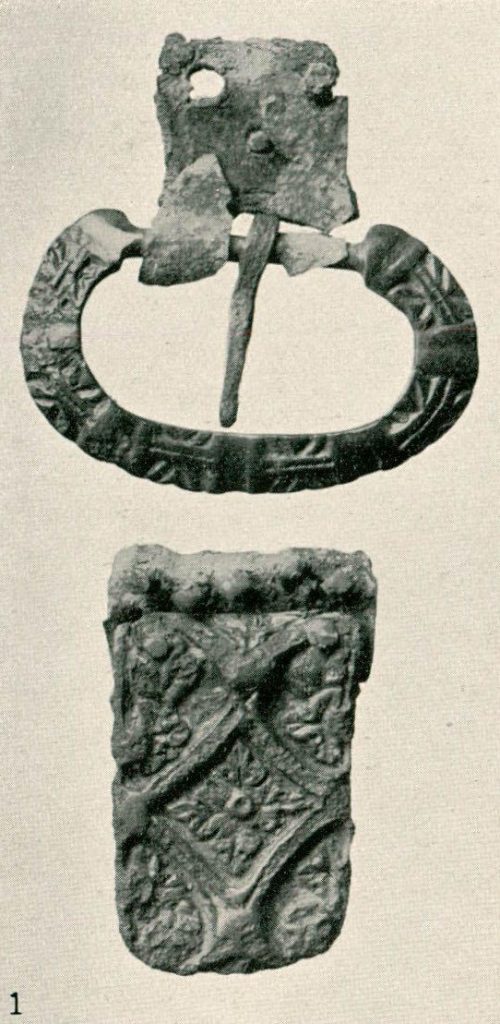

One of my winter projects is recreation of the carolingian silver belt buckle and strap-end from Bj750 (which might or might not have been the woman’s belt, as the grave is a double grave). I plan on using it for a new sword belt.

I bought a very nice replica from Gudred, my usual vendor for anything cast in bronze or silver. This replica is, however, not strictly speaking a 100 per cent replica, and maybe rightly so.

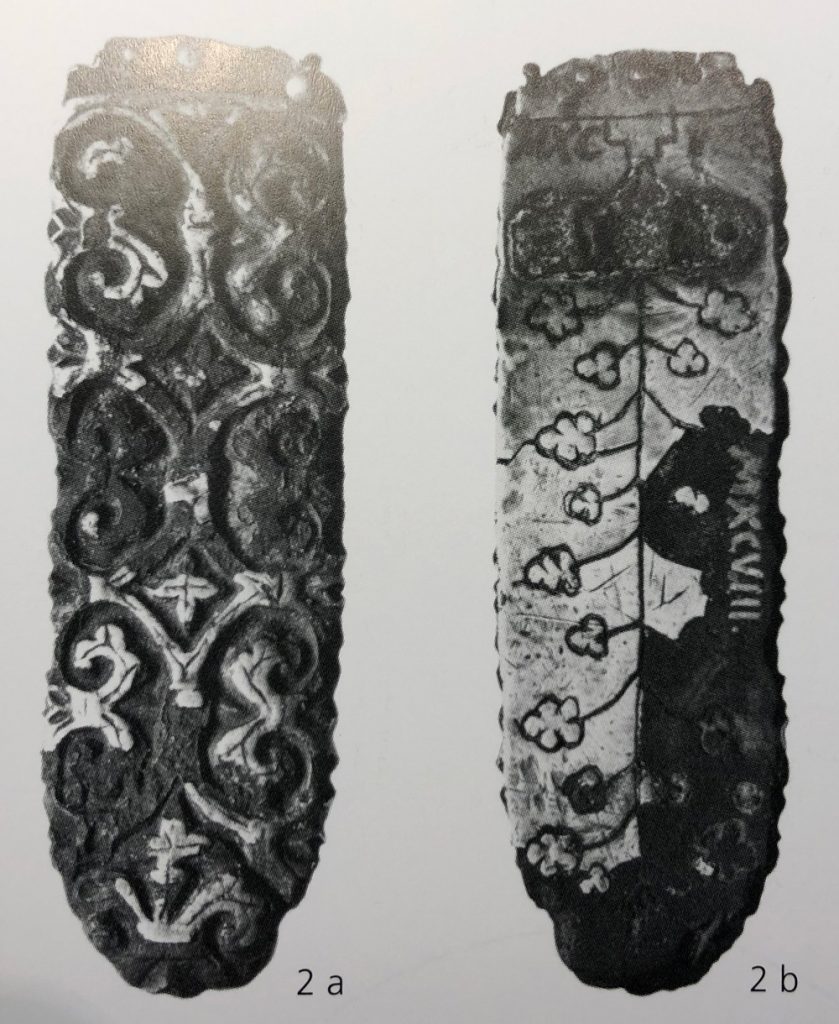

The original finds, especially the strap-end, were modified, damaged and worn. This might be because they were already old when they were put to rest in Bj750, but also because they might have been used as „spare change“ at some point. The image from Birka I:Tafeln shows the original finds, but some construction details are hard to spot.

The strap-end is more round, even tongue-formed, than the replica. This is quite certainly due to wear, maybe also because the use as a strap-end was not its primary usage. There are trefoil brooches in carolingian design which ended up as strap dividers, and as pendants.

Anyway, I suspect that the item was not originally rounded, as the curve is not symmetrical (which it would be if it had been cast round, as numerous examples from other findplaces show). A small detail that can hardly be seen from the picture is the fact that the strap-end has been adapted for usage as a belt.

The picture above shows that there are not two rivets (as would be normal for a strap-end that is mounted at the end of a belt), but in fact seven. The rivets highlighted in red are either the original rivets (if the find was never anything but a strap-end), or rivets from the primary modification. They were then used to rivet a small silver plate (seen at the top border, overlap is visible on the top-right edge) to the strap-end. That silver plate has, in turn, five own rivet holes which were used to rivet it to the belt strap.

This method has two advantages:

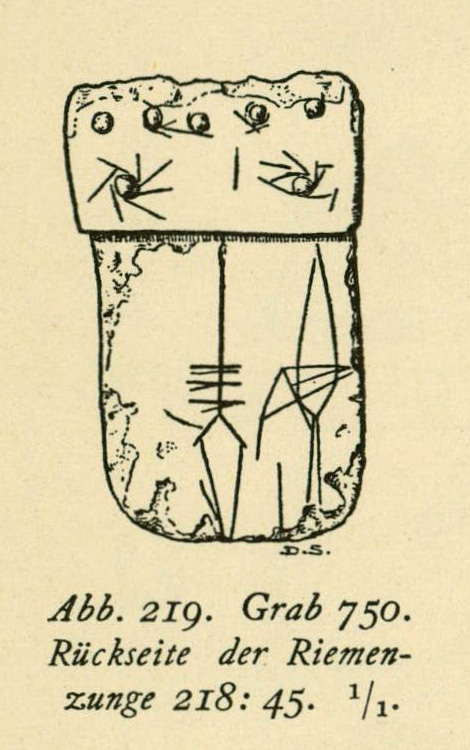

More interesting about this strap-end is the fact that it’s in fact decorated – if you want to call it that – on its back, too. This is a picture from Birka I: Die Tafeln.

The primary and secondary rivets can be seen clearly, as well as scribbled decoration. Maybe this is supposed to show some religious or spiritual beings, has ritual meaning or someone was simply bored. Birka II likens the shapes to spears or arrows.

Either by sheer accident, or on purpuse, the vertical line and the arrow-shape on the backside is in line with the frontal decoration’s symmetry axis. The text in Birka II:2 (p110) describes the spear-decorated part as „a piece of silver sheet metal riveted to the strap-end“, which is either a mistranslation or simply wrong, because the lower part obviously seems to be part of the cast strap-end.

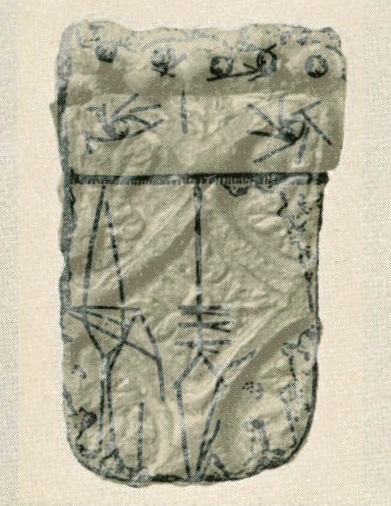

The strap-end in this picture was found close to the castle („Hochburg“) from Hedeby in 1812, the picture is from Arents/Eisenschmidt, die Gräber von Haithabu.

This strap-end shows very similar acanthus decoration, a more deliberate rounding at the end and – it’s decorated on the back, as well. This decoration looks a lot more purposeful than the one in Birka.

Yet another very close parallel is this find from Hedeby. Unfortunately, the findplace is unknown, it was prospected by Jankuhn and first published in his 1934 book about Haithabu. It’s a rectangular bronze part of a belt mount (?) with secondary usage as a fibula or brooch.

My question is: Should I mimic the repairs/reporpusing and the amateurish decoration, not knowing what it was intended for? Should I deliberately age and damage the replica?

The people who wore this belt clearly valued it so much that they not only repaired it several times to keep it in service, but also gave it to the deceased in their grave. Would they have access to the „nice“ version with clear edges, and no repairs, they would have used it, I presume.

However, the worn and secondarily decorated look is more accurate as a representation of the item’s *current* state.

What would you do? I’d love to read your opinions!

One of the parts of my kit that I was kind of ashamed for was my shield glove. I took great pains to have a halfway decent looking glove for my sword hand (although compromises had to be made there, too), but the glove for my shield hand was a welder’s glove. Practical but ugly.

I had a todo for „new shield glove“ since at least April 2016, but I didn’t quite get around to it. This weekend, after making a practice piece from artificial leather, I went for the real thing. I took some pictures to illustrate the process.

There are some „truths“ in reenactment which are rarely questioned, although maybe they should be. These are sometimes called „reenactorisms“, self-propagating myths that are perpetuated by the „monkey see, monkey do“ attitude that befalls reenactors, be they inexperienced or veterans.

A reenactor’s knot (image copyright The Jelling Dragon)

One of those truths is a trivially sounding question: How long were viking-age belts? We have come to accept that they had a buckle and a strap-end, and the strap-end hung about crotch to mid-thigh – 20 to 40 cm from the buckle. The strap was fed through the buckle and then knotted just behind it, hanging straight down. This is sometimes called „the reenactor’s knot“, and there doesn’t seem to be an awful lot of evidence for it. Apart from that, it is really impractical because you constantly have a strap-end dangling between your legs. 😉

So, an excellent reenactor and designer of bronze jewelry replicas, Burr Öhrström, took it upon himself to research the Birka graves for evidence of belts and buckles. I did the same tonight (oblivious of the fact that he already had done that) and would like to systematize the conclusions a little.

Helmets are a bit of a touchy topic for viking-age reenactors. There really aren’t that many finds from the „Viking lands“, i.e. Scandinavia, the British Isles and the Rus area of influence.

In the West, there’s the Gjermundbu helmet – an iconic helmet that is for many people the definition of a „viking helmet“. However, that helmet is a singular find, and it’s from Norway. From what is now Poland and Czech Republic, there are several nasal helmet finds (St. Wenceslas‘ helmet with Christ Savior nailed to the nasal, Lednicki lake, Olmütz, to mention a few) and the Rus have helmet finds from Cernigov (actually, several from that area, but I’ll cover that in a second), from Gnezdowo (a simple nasal helmet, as well as an „Eastern“ helmet with brass decoration) and some more (see below).

There’s a good overview over Russian helmets on Peter Beatson’s site, taken from Volume 3 of Kirpichnikov’s seminal anthology on Old Russian Arms and Armour.

There are very few finds of viking-age helmet remains in what is now Sweden, unfortunately. There is the Lokrume fragment from Gotland (which, due to its specific geography, is stilistically so far removed from mainland Sweden that it could well be a completely different country), and that’s pretty much it.

Des Mannes braune Wolltunika mit Wildseidenbesatz ist seine liebste Tunika – aber leider nicht so richtig authentisch. Die Wildseide wäre in Birka vermutlich als Tischdecke verwendet worden (gefundene Kleidungsseide war sehr, sehr fein verarbeitet und nicht von der groben, „rustikalen“ Art wie Wildseide typischerweise ist) und die Besätze sind auch etwas zu breit. Aber sie hat lange gehalten und wird auch sicher nicht einfach so aufs Altenteil geschickt.

Über die Jahre reifte der Plan, mal was Neues zu machen. Durfte ruhig schick sein, aber nicht überkandi delt (und nicht zu weit jenseits des Fundguts). Broschierte Seide, wie sie derzeit modern ist, schied also aus. Nach längerem Suchen entschied ich (wenn ich die ganze Zeit von mir in der dritten Person schreibe, werde ich rammdösig) mich für eine blaue, indigogefärbte Wolle von Jörg und chinesische Seide von Kaptorga, die ich allerdings in letzter Minute gegen eine rotholzgefärbte Seide von Susan ausgetauscht habe. Als zusätzlichen Schmuck habe ich eine sehr schöne Reproduktion der Borte B13 aus Birka, Grab 735 erworben. Die ist als einziger Bestandteil der Tunika rein „chemisch“ gefärbt.

delt (und nicht zu weit jenseits des Fundguts). Broschierte Seide, wie sie derzeit modern ist, schied also aus. Nach längerem Suchen entschied ich (wenn ich die ganze Zeit von mir in der dritten Person schreibe, werde ich rammdösig) mich für eine blaue, indigogefärbte Wolle von Jörg und chinesische Seide von Kaptorga, die ich allerdings in letzter Minute gegen eine rotholzgefärbte Seide von Susan ausgetauscht habe. Als zusätzlichen Schmuck habe ich eine sehr schöne Reproduktion der Borte B13 aus Birka, Grab 735 erworben. Die ist als einziger Bestandteil der Tunika rein „chemisch“ gefärbt.

Der Zuschnitt der Tunika war für mich die größte Hürde – mit dem Zuschneiden von Kleidung, besonders bei hochwertiger Wolle, tue ich mich noch immer schwer. Irgendwann waren dann alle Stücke ausgeschnitten und ich habe jedes einzelne mit waidgefärbtem Wollgarn handvernäht. Das dauerte seine Zeit und nach der Aktion war auf einmal April. Mittlerweile war die Borte da und die Nervosität wuchs. Ich hätte mal mehr als 1m bestellen sollen.

Erste Stellproben wurden mit diversen Facebook-Gruppen besprochen. Das Ergebnis war nicht eindeutig.

Nach längerem Probieren habe ich die Borte dann in 20cm-Stücke geschnitten und die Enden umgelegt und fixiert.

Das Ganze mußte dann „nur noch“ auf die Seide als Trägermaterial aufgenäht werden – im Fund in Bj735 war auch die Borte auf ein Stück Seide genäht. Das ergibt bei einem so teuren Besatz auch Sinn, denn war das Kleidungsstück, auf dem er saß, kaputt (oder unmodisch geworden), konnte der Besatz abgetrennt und weiterverwendet werden.

Beim Nähen von silberner Drahtborte auf die Seide wurde es lustig. Mit Stecknadeln fixieren ist bei Silberdraht vs. Seide ein Alptraum (das eine Material ist hochflexibel, das andere so starrsinnig wie ein Ostwestfale), also habe ich mir von Lisa den Tip geholt, die Borte schnell mal festzusteppen. Und dann ging’s auch mit dem Vernähen.

Nächster Schritt: Seide auf Wolltunika nähen. Das war beim Quadrat mit der Borte noch einigermaßen friemelig, aber als ich mich vom Gedanken verabschiedet habe, auch nur eine wirklich gerade Kante zu haben, ging es dann.

Danach fehlte noch ein bißchen Besatz für die Ärmel – das war dann verhältnismäßig einfach. Die Besätze sind 2cm breit, was vermutlich sogar schon am oberen Ende für die wikingerzeitlichen Besätze war (1cm oder weniger war vermutlich nicht unüblich) – aber ich habe nicht die handwerklichen Fähigkeiten, um mit einem so dünnen Besatz klarzukommen. Noch nicht.

Zum Vernähen der Seide habe ich glücklicherweise Seidengarn aus derselben Färbung verwenden können, das praktisch überhaupt nicht sichtbar ist. Trotzdem habe ich mit extra kleinen Stichen (wieder: Für meine Verhältnisse, die Originalfunde sind teilweise mit kleineren Stichen vernäht als moderne Maßhemden!) genäht.

Und dann war irgendwann der letzte Faden versäubert und die Tunika fertig. Um die Halsöffnung schließen zu können, habe ich noch einen Kaftanknopf nebst Schlaufe angenäht, das ist aber erstmal eine temporäre Lösung.

Und so sieht die fertige Tunika aus.

I made a new tunic for myself, based on finds from Birka. The wool is indigo dyed tabby, hand sewn with indigo or woad dyed wool thread. The silk used is redwood dyed fine silk, sewn onto the base wool with redwood dyed silk thread.

The braid is based on Birka B13 braid from Bj735 and sewn into 5 „ribs“ (original had around 8, and some diagonal crossing) onto the silk. The braid is made from silk warp and silver weft, probably not indigo but artifical dye, but very close in colour tone.

[I think there’s a demand for an english version of this article, so I’ll translate it.]

This blog suffered from our preference of facebook lately. That has many reasons, one of them being bigger intensity and quantity of interaction (albeit not quality!). We have had a lot of discussions about reenactment topics, many of them tiring, most very interesting. One of the more tiresome topics regards a „reenactorism“, a self-perpetuating myth that has been created by reenactors and is now often taken for a fact.

In an irregular manner, I will pick up some of these reenactorism and give them a fact check.

Today: The Varangian Guard. Legguard, not Guardsman. Actually, leg and arm guard, not Guardsman. Just a couple days ago, I saw someone selling „varangian armguards“ online, and I shivered. These devices are the impersonification of reenactorisms for me. But let me begin at the beginning…. or actually at the end.

Dieses Blog ist nicht zuletzt inhaltlich in den letzten zwei Jahren sehr ins Hintertreffen geraten, weil wir uns deutlich mehr auf Facebook als hier engagiert haben. Das hat viele Gründe, einer ist aber sicher die doch höhere Intensität und Quantität (wenn auch vielfach nicht Qualität) des Feedbacks. Wir haben viele interessante, teilweise auch ermüdende Diskussionen zu Reenactment-spezifischen Themen geführt. Eines davon sind immer wiederkehrende, aber nicht mit Fakten zu untermauernde Mythen des Reenactor-Daseins – die sogenannten „Reenactorismen“ oder „Reenactorisms“.

Ich werde in den nächsten Monaten immer mal wieder einige dieser Themen, die auf Veranstaltungen oder in Online-Diskussionen häufig wiederkehren, aufgreifen und auf ihren Wahrheitsgehalt abklopfen.

Heute: Die Warägerschiene. Just heute morgen sah ich im Facebook-Feed die Anzeige eines Händlers aus der Wikiszene, in der „Waräger-Armschienen“ zum Verkauf standen und bekam eine Gänsehaut. Handelt es sich bei diesen Gerätschaften doch um einen Gegenstand, der den Inbegriff eines Reenactorismus‘ darstellt. Aber von vorne…