Disclaimer: I am not judging whether viking-age northern Europeans („Vikings“) had tattoos or not. I am merely analyzing the main source for this claim on a linguistic and source-critical basis.

TL;DR

We don’t know and Ibn Fadlan is not a good primary or secondary source for vikings with tattoos.

Introduction

The question whether or not vikings wore tattoos is as ambivalent as controversial. As tattoos have entered the mainstream, many reenactors and viking enthusiasts (myself included) sport some viking-themed ink. And from the ubiquitous (and not viking-age) „Vegvisir“ symbol over runic inscriptions to copies of ornamental artefacts on human skin, the repertoire of tattoos with a viking theme is abundant.

However, this article does not aim to answer that particular question. I would like to shed some light on the most-quoted „source“ for vikings with tattoos.

The travel account of Ahmed Ibn Fadlan ibn al-‚Abbās ibn Rāschid ibn Hammād (known to his friends as „Ibn“ 😉 ) contains a passage in which he describes his encounter with what he calls the „Rusiyyah“ at the river Volga. This encounter was fictionalized in Michael Crichton’s „Eaters of the Dead“, a novel which eventually turned into the movie „The 13th warrior“ with Antonio Banderas. While the movie adaptation of this scene is in some passages quite close to the original account, it’s far from certain that the group of people encountered by Fadlan were in fact what we today call „Rus“ or „Vikings“.

James E. Montgomery has this to say on the matter in his paper „Ibn Fadlan and the Rusiyyah„[1]James E. Montgomery – Ibn Fadlan and the Rusiyyah, 2000, available online: http://www.unm.edu/~doug/montgomery.ibnfadlan.2000.pdf:

I am not convinced that by Rus/Rusiyyah our text means either the Vikings or the Russians specifically. I am neither a Normanist nor an anti- Normanist. The Arabic sources in general quite simply do not afford us enough clarity.

James E. Montgomery – Ibn Fadlan and the Rusiyyah (Cambridge, 2000)

The main issue, however, is a linguistic one. For many years, there was no original manuscript of Fadlan’s travel accounts, and most scholars were either working with copies or even translations, and errors propagated heavily.

Frähn’s translation and critical remarks

I have a PDF of the book „Ibn-Foszlan’s und anderer Araber Berichte über die Russen älterer Zeit“ by C.M.Frähn[2]C. M. Frähn, Ibn-Foszlan’s und anderer Araber Berichte über die Russen älterer Zeit, 1823, available online: https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_xXlqPiJsMsgC, which is a critical and heavily annotated translation[3]And by „heavily annotated“ I mean that there’s frequently one line of manuscript per page, with the rest of the page taken up by annotations. It’s not an easy read. from 1823. Frähn didn’t work with an original, but a copy, and he, together with Montgomery’s modern english translation of the text, are my main sources for this article.

In his description of the Rusiyyah, one specific sentence is the source for all the tattoo discussions. It is this sentence:

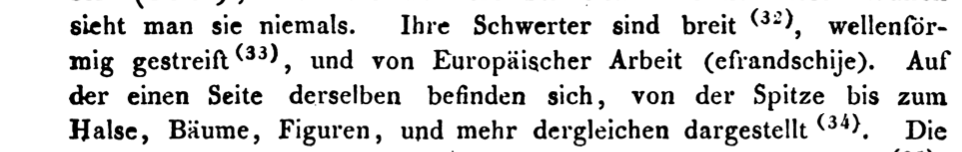

„Their swords are broad, patterned with waves, and from European work. On one side of these there are, from the tip up to the neck, trees, figures and more.“

Frähn’s translation of Ibn-Fadlan’s description of the Rusiyyah, tr. to english by the author.

Please note that according to this translation, the passage about the trees, figures and more doe not apply to the men but to their swords, because the word „derselben“ can grammatically only belong the the subject of the previous sentence, not the sentence before that.

There’s an annotation (34) next to the end of the sentence, and this annotation is actually quite long.

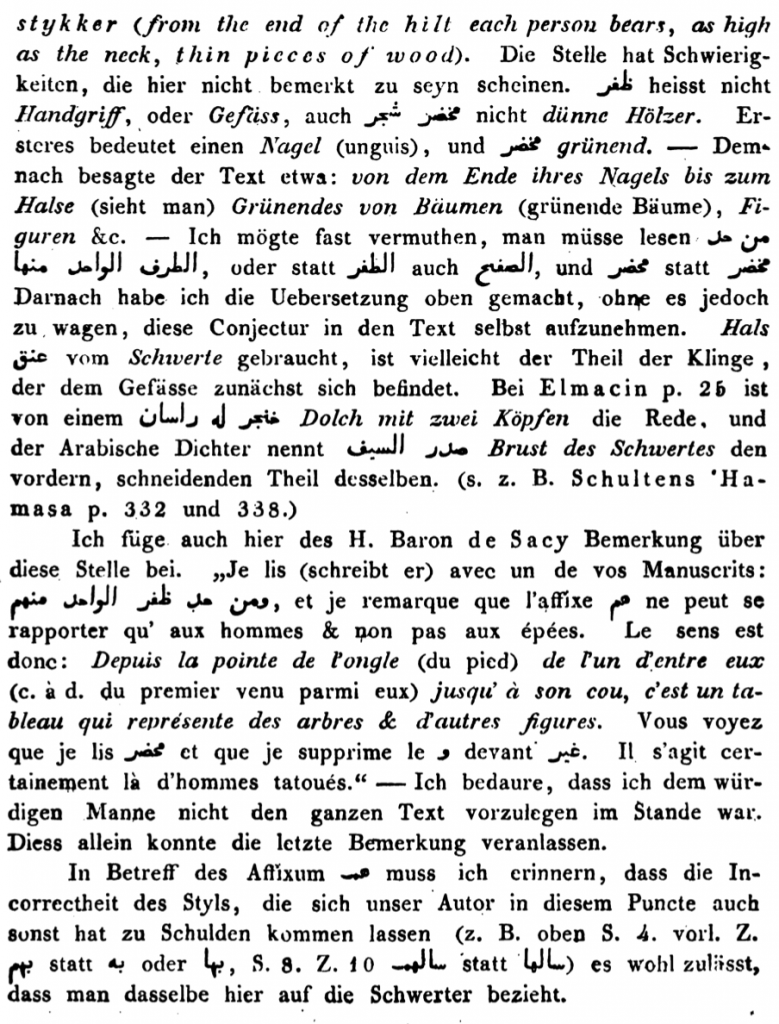

Okay, this is long and confusing, and contains at least five different languages[4]In case you’re too lazy to count, there’s Danish, German, French, Arab and English, so I’ll try to summarize it. Frähn first cites the english translation of a danish translation, which goes like „each person bears [..] thin pieces of wood“, an obviously incongruent translation. He writes that „this passage has issues which seem to have gone unnoticed.“

Frähn then goes on to compare the cufic letters of the Arabic text to more logical meanings, and translates to „from the end of their nails up to the neck, one can see green trees“. Frähn then surmises that the body parts are indeed the parts of a sword, with the neck being the part closes to the hilt.

However, another translator, a „Baron of Sacy“, has remarked that the in his opinion the text must refer to humans, not to swords, and that the translation should be as follows:

From the tip of the nail (of the foot) of one of them to his neck, it is a table which represents trees and other figures

Author’s english translation of a french interpretation of the arab text… I’m getting a headache.

Almost 200 years ago, there was a healthy debate about this one sentence, and remark 34 does not end here. The author then complains that

Regarding the affixum [cufic character] I must remind that the incorrect style, which the author [he means Fadlan] is guilty here and in other places [a list of other caligraphic errors] allows us to interpret this character as belonging to the sword

Author’s english translation of Frähn’s remark, passages in [] are the author’s remarks

After reading through the passage and the remarks, it only remains to say that Frähn’s text is completely inconclusive. It seems to be equally likely that the decoration belongs to swords and to humans.

Montgomery’s translation in „Two Arabic travel books“

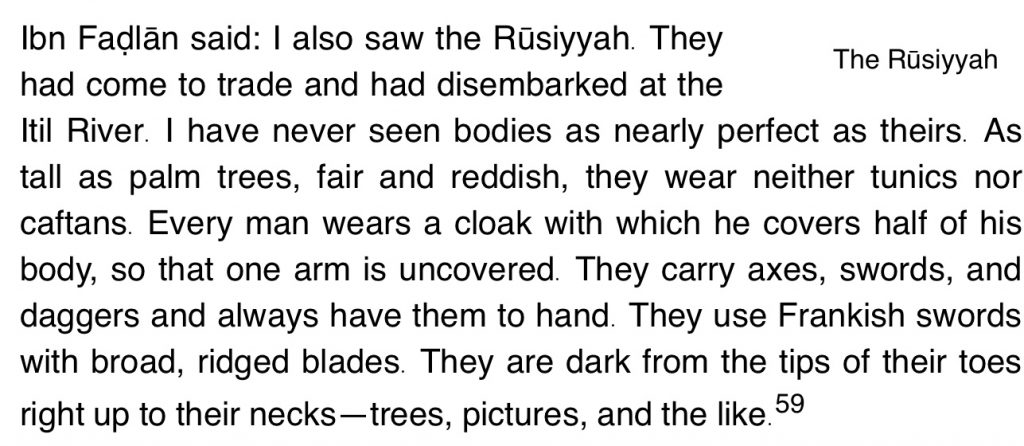

In the book „Two Arabic travel books“ by T. Mackintosh-Smith and James E. Montgomery[5]Mackintosh-Smith, Tim, Abu Zayd al-Sirafi, James Montgomery, and Ahmad Ibn Fadlan. Two Arabic Travel Books: Accounts of China and India and Mission to the Volga. New York: NYU Press, … Continue reading, there is a new translation of this phrase by Montgomery.

Here, we have a clear translation that attributes the trees and pictures to the… wait, to „them“, does this mean the Rusiyyah or their swords? And what does annotation 59 tell us?

This phrase is obscure and the Arabic syntax is far from clear. Ibn Fadlan is thought by many to be describing tattoos of trees and other forms, but the practice of tattooing is unattested for the Vikings and he may mean that they have the images of trees and other shapes painted on them, perhaps using a plant dye.

Annotation 59 in Two Arabic travel books, confusing reenactors even further.

This opens up a third interpretation – non-permanent decoration on the Rusiyyah men’s bodies, something like „war paint“. Not helping.

Summary – is Ibn Fadlan a witness of tattooed vikings?

All in all, we simply cannot say if Ibn Fadlan’s story describes tattoos, because the Arabic writing is too ambivalent to interpret.

In my opinion, this means that reenactors, tattoo artists, movie producers etc. should not cite Ibn Fadlan as the primary evidence for tattoos on vikings.

References

thank you for clearing and not clearing this up, i enjoyed reading it, and i appreciate your research. I still like the idea of having tattoos in a viking theme also because it keeps the history alive although not completely correct… i also am quite curious about other European civilizations and there appearance, for instance the cythian , they had remarkable tattoos also